Effective management of public commercial assets can transform the way that business is done, but also be a driver of productivity and fiscal space. The importance of well-governed public assets cannot be overstated, as they often operate in important sectors such as transport, energy, and finance, as well as real estate on which the broader economy depends.

A government owner of commercial assets faces many conflicts of interest. Not the least with its role as a regulator of the business sectors where it also has an ownership stake. This is why commercial assets owned by the public sector are best held and governed in a separate eco system – a Public Wealth Fund (PWF) - away from the line ministries.

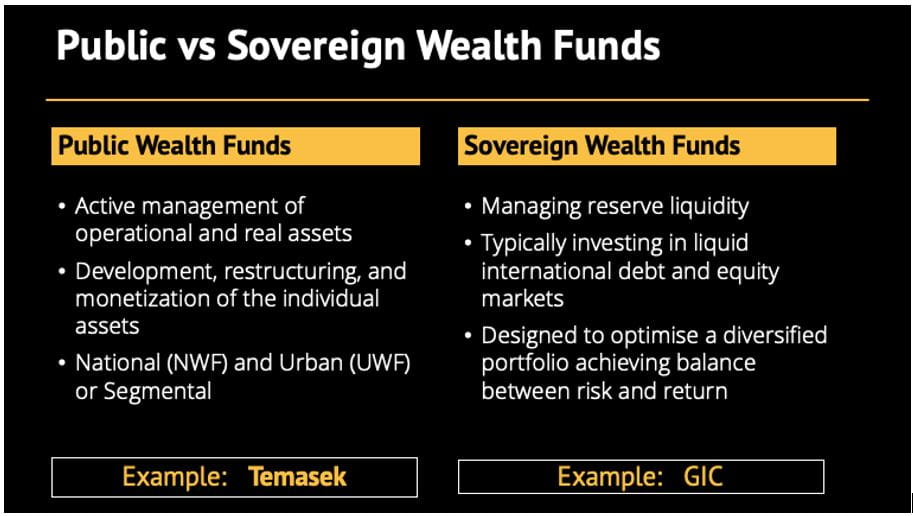

This is different from a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) such as the GIC in Singapore, which is primarily concerned with managing reserve liquidity, typically investing in securities traded on major mature markets. SWFs are designed to optimize a portfolio by trading securities to achieve a balance between risk and returns. A PWF is a fund for managing a portfolio of operational assets with a view to maximizing the assets’ value.

The managers of such a fund should be at arms-length from short-term political influence and have the ability to use all the tools available in the private sector for professional management of the assets, including proper accounting - as if the fund were a listed business.

Importantly, a PWF is like fire – it can be a powerful force for good but can also do great damage Perhaps the best example is Temasek, the Singaporean PWF that has generated a compounded and annualised return of 14 per cent since its inception in 1974. Together with GIC the two holding companies manage a portfolio worth more than twice GDP. The government has put in place mechanisms to safeguard the nation’s accumulated net worth (‘Reserves’) from being potentially frittered away by future governments. These Reserves have the dual role of providing a stream of investment income, as well as serving as a rainy-day emergency fund.

In the wrong hands, a PWF can also be used against society, such as in the case of the many such funds controlled by the military in countries such as Egypt, Pakistan, and Myanmar. Or the 1MDB, the PWF of Malaysia, where more than US$4.5 billion was diverted to the benefit of government officials, including the prime minister Najib Razak and other conspirators. This is why such a powerful tool requires a robust network of stakeholders and safeguards to prevent it from being misused.

International research shows that a majority of countries are increasingly moving towards consolidating the ownership and governance of public commercial assets held by many different government ministries and agencies, under a centralised model of ownership and governance.

This might not seem very difficult, but it requires the political will to move substantial wealth away from the control of line ministries to a PWF, overseen by the ministry of finance. In this way the assets can be used not as a policy tool but as a financial instrument to improve fiscal space and improve debt sustainability.

Any political compromise by using some alternative governance models are likely to result in weak governance with opposing objectives, political interference, and a lack of public scrutiny. Examples of this can be found in Greece and Ukraine where nominal governance structures have been established that act as mere advisors. This results in either preserving the status quo, where the entities act as a policy tool, or privatisations without proper due process, resulting in an undue transfer of public wealth to the private sector.

Finland divided the ownership structure of its commercial assets into two separate portfolios. Listed shareholdings were consolidated inside Solidium, the Finnish PWF, yielding a total return on its portfolio of 10 per cent per annum since inception in 2008.

Through a political compromise, the remaining holdings were assigned to the Prime Minister’s office, instead of the Ministry of Finance. This decision resulted in much lower returns, but also had a political cost. When the Finnish postal workers went on strike in 2019, it ultimately forced the resignation of the Prime Minister Antti Rinne who was replaced by Sanna Marin, the current Prime Minister.

Any compromise in the fundamental pillars of good governance for public commercial assets - which include transparency, clear objectives and political insulation - would instantly be translated into lower returns for the portfolio and for the individual assets. It would also result in a ‘political’ discount on the price a potential investor would be prepared to pay when considering investing in a government linked asset, as it would not be seen as fully commercial.

An independent holding company at arms-length from political influence is the start of the journey and is best able to navigate between the business requirements of commercial assets and the political reality. The optimal outcome is achieved when there is the political will and a network of stakeholders such as international bondholders and shareholders to require professional management as if the assets are entirely owned by the private sector.